In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly designated October 2nd the International Day of Nonviolence in honor of Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday. It feels particularly important to reflect on what it means to reaffirm Nonviolence as a way of life as news of escalating violence has been arriving from so many different places in recent days.

The M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence is a place that has deepened my understanding of how to translate nonviolent beliefs into nonviolent practices. As a neuroscientist who has researched how our brains turn ideas and intentions into actions, I view the nonviolence and de-escalation workshops offered by the Gandhi institute as brain-building experiences. Here are some reflections on the connections between Gandhi’s principles of nonviolence and the brain circuits we can nurture for peacemaking.

Nonviolence reaffirms the reality of our interconnectedness. Violence arises from oversimplified cause-effect thinking, imagining each person as a discrete, isolated entity. But humans are a social species with highly specialized brain areas evolved for empathy, imagination, complexity, and collaboration. Building our capacity for nonviolence uses these specialized brain areas, revitalizing our sense of place as interconnected beings in the complex ecosystems of life on earth. In Gandhian nonviolence, reconciliation is the aim, not defeat; eliminating harmful actions is the goal, not eliminating human beings.

Nonviolence extends curiosity toward what life is like in another’s shoes. Violence is fundamentally un-curious. Finding alignment with others in the face of disagreement can seem daunting, but curiosity enables us to learn the deeper context of how misalignments emerge, which often uncovers threads of connection and commonality that can serve as the starting place for reconciliation. In his articulation of Satyagraha, or “Truth-force”, Mahatma Gandhi points out that “what appears to be truth to the one may be error to the other” and commitment to truth “excludes the use of violence because man is not capable of knowing the absolute truth and, therefore, not competent to punish.”

Interestingly, brain imaging studies of aggression have found altered activity in areas of the brain involved in interpreting the motives of others. If we view this as a brain rehabilitation challenge, I imagine that practicing empathy (a core practice in MKGI’s Nonviolent Communication workshops) is how we boost the function of the social imagination components of a nonviolent brain.

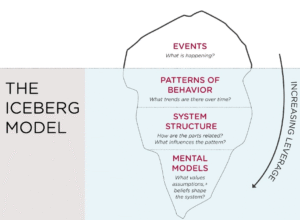

Nonviolence emerges from patient persistence. Violence is impatient, seeking a quick, seemingly simple “direct corrective” to disagreement. Gandhi wrote that “pursuit of truth did not admit of violence being inflicted on one’s opponent but that he must be weaned from error by patience and sympathy.” Neurobiological research highlights impulsivity as a common feature of violence and aggression, with studies showing altered brain activity in areas involved in processing expectation and buffering reactivity to negative stimuli. When I think about how to build a brain that is less prone to reacting with aggression, I think about connections from the “higher brain” prefrontal cortex to more reflexive “downstairs brain” circuits–inhibitory connections that are essential for pausing before acting. Meditation and other mindfulness practices are one toolkit that can help boost these connections. Networks of relationships that foster a sense of trust and safety are also essential for helping brains to be less primed for reactivity; this is why the Gandhi Institute’s “Help Zones” in RCSD schools are an important part of building nonviolence capacity in the brains of our young people.

The foundation of nonviolence is courage. Violence is rooted in fear. Gandhian nonviolence is not simply the passive absence of violent action; it is the active presence of courageous action in pursuit of justice. Courage is not the absence of fear, but rather taking right action in the face of fear. Harm-avoidance is strongly primed in our downstairs brain, so it takes active practice and cultivation of intention to transcend fear and embrace risk in service of justice.

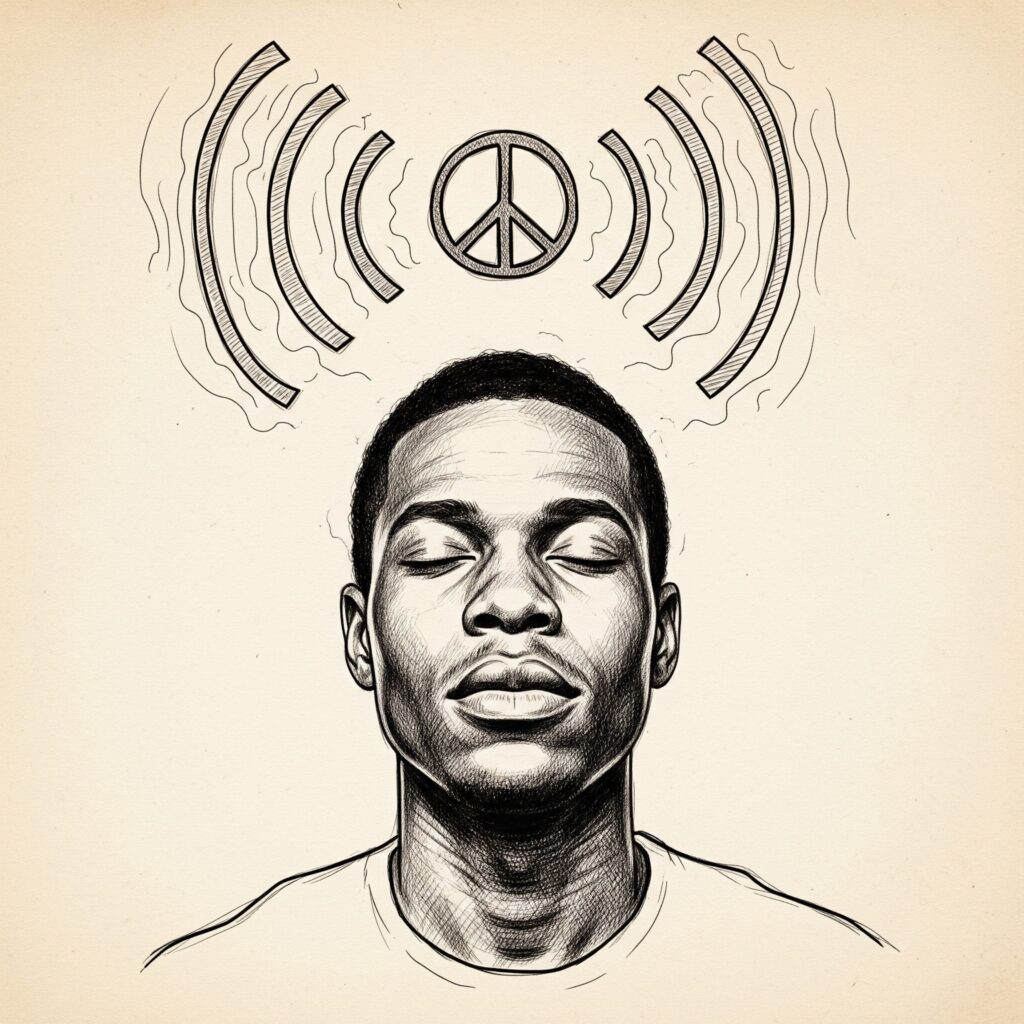

I sometimes visualize our brains as biological radios through which the fundamental frequencies of the universe are filtered. The things we choose to amplify or suppress shape our brain circuits, which then shapes the blend of frequencies our radios transmit. Without intention, and without practice, we sometimes transmit harsh noise. With intention, and with practice, we can learn to tune our brain radios to transmit harmony. We hear about acts of violence and threats of violence in the news, because fear sells; but there are courageous acts of resistance and healing happening everywhere. Rivera Sun’s Nonviolence News is one excellent source for stories of courage. Rebecca Solnit’s Meditations In an Emergency is another source I follow for collated stories of people resisting the administration’s abuses of human rights. A recent piece amplified this quote about hope from Vaclav Havel (from Disturbing the Peace):

“. . . [T]he kind of hope I often think about (especially in situations that are particularly hopeless, such as prison) I understand above all as a state of mind, not a state of the world. Either we have hope within us, or we don’t. . . . Hope is not prognostication. It is an orientation of the spirit, an orientation of the heart. It transcends the world that is immediately experienced, and is anchored somewhere beyond its horizons. . . .Hope, in this deep and powerful sense, is not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously headed for early success, but rather an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed. The more unpromising the situation in which we demonstrate hope, the deeper that hope is. Hope is not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out. In short, I think that the deepest and most important form of hope, the only one that can keep us above water and urge us to good works, and the only true source of the breathtaking dimension of the human spirit and its efforts, is something we get, as it were, from ‘elsewhere.’ It is also this hope, above all, that gives us the strength to live and continually to try new things, even in conditions that seem as hopeless as ours do, here and now.”

Hope as an orientation of the spirit feels very akin to Gandhi’s Satyagraha: a calling forth of the our capacity as human beings to work toward justice and mutual care and beloved community, tuning into those fundamental frequencies of the universe regardless of the state of the world. This is the kind of music the human species is meant to broadcast. The Gandhi Institute is one place where we can learn to more skillfully tune our brain radios to the harmonies of Nonviolence. Join us at an upcoming workshop! You can also donate to support the Institute’s work in the community here.